Inventing the Future

January 2001 - Northern Ohio Live - Probing Minds

Cleveland neurosurgeons are pushing the boundaries of a new cerebral technology

BY ANTON ZUIKER

Over the cackle of static, Abed Hammoud whispers to me through his surgical mask: "This is the frontier of medical technology."

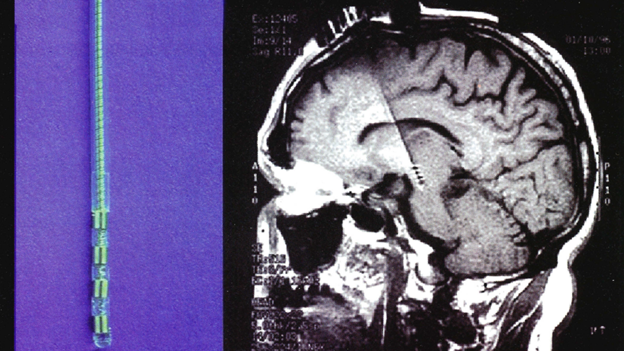

Hammoud is not a surgeon. He has a PhD in biomedical engineering and works for Medtronic Corporation. This snowy morning in December, he is in Operating Room Number Eleven at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation. He is operating the Silicon Graphics computer and Medtronic's software that is allowing Clinic neurosurgeons Ali Rezai and Erwin Montgomery to ever so slowly push an electrode the size of a hair deep into the brain of a man named Russell Purdue, in a procedure called deep brain stimulation (DBS).

DBS is a new surgical treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson's disease, epilepsy and multiple sclerosis - all of which can cause immobilizing tremors in a person. ("It's as if you're driving with the parking brake on," says Rezai.) The Cleveland Clinic is the leading center for DBS in the United States.

Russell's Case

Russell, a construction worker from West Virginia, has multiple sclerosis; his case is more difficult than the Parkinson's cases that Rezai has mastered, but the procedure is the same. The surgical team will find the "sweet spot" in an area of the brain called the subthalamic nucleus that, when stimulated with the electrode, will shut down - stopping the tremors.

The peculiar noise filling the operating room, I learn, is not merely white noise to help the patient sleep - Russell is awake and responsive; it's actually the sound of Russell's brain.

What sounds like AM radio static mixed with Morse code are the conversations of neurons sending electrical signals back and forth. Montgomery eagerly follows this dialogue, for he's learned how to use the signals to help him pinpoint where in the brain the electrode is now resting. "It's like traveling from eastern Europe to western Europe along a highway," says Montgomery. "First you hear Polish, then you hear German."

The Development of DBS

Montgomery first heard the sounds of brain cells in the laboratory of Nobel laureate Sir John Eccles, neurophysiologist. "I just thought that was the coolest thing I'd ever heard, and I decided that's what I wanted to do."

Keep traveling on Montgomery's highway, and you'll make it to Grenoble, France, where the father of DBS (as Rezai calls him) teaches neurosurgery. In surgical procedures called pallidotomy and thalamotomy, surgeons destroy parts of the brain to stop tremors. During those procedures, the surgeons use an electrode to find the correct area to treat. In 1987, professor Alim-Louis Benabid, M.D., noticed that this stimulation of the thalamus mimicked the effect of the destructive surgery. So he developed DBS.

Technology and Innovation

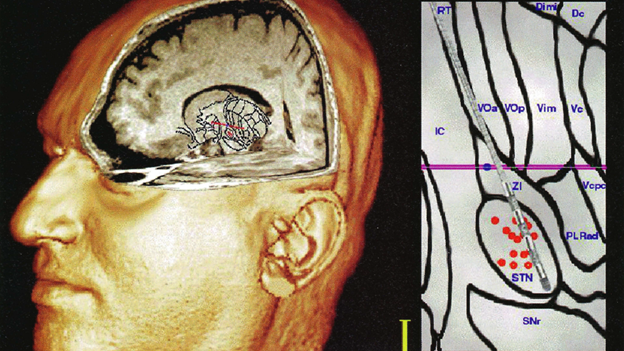

Rezai and Hammoud eagerly demonstrate how the software morphs a CT scan with an MRI picture together with an overlay of topographical lines into a 3-D image of the brain, giving the surgeons a figurative road map to Russell's thalamus.

"The thalamus is the Grand Central Station of the brain," Rezai had told me earlier. It's this small area at the center of the brain, divided into 120 sub-regions, which routes the body's signals to move. Rezai expects that the electrode he implants in Russell's thalamus will "quench the chaotic neuron activity" that makes him twitch and quiver.

Grill received a $1.6 million, five-year grant from the National Institutes of Health to answer this fundamental question: Which neuronal elements are affected by the stimulation – the local neuron cells touched by the electrode or the passing axon output flowing between those cells? He uses computer-based models to do his testing and relies on Dr. Montgomery's clinical research to corroborate the computer.

Future of DBS

"The hope is that all doctors will one day be as comfortable prescribing electricity as they are prescribing medication," says Montgomery.

Rezai expects that, any day now, the FDA will grant final approval to DBS as a standard treatment for Parkinson's tremor. Other emerging areas for DBS use are epilepsy, chronic pain and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

In June 2001, Cleveland will host the international symposium Functional and Restorative Neurosurgery: Defining the Future. "Fifty of the world's leading authorities and pioneers on neuromodulation - the All-Stars - will be here for three days," says Rezai. "It will be exciting to bring these minds together to chart the course of neurosurgery."

One possible innovation, says Mayberg, is a "radical online collaboration to share data intraoperatively, in real time. Dr. Benabid has a grant from Telecom France. He'd be on-line with a video link and would be looking at the same information on his computer. It may seem far-fetched, but someday he might even drive the movement of the electrode. As the technology expands, we may become a center for doing operations around the country."

And then, probing minds will listen in as the brain talks.

Northern Ohio Live | January 2001